W.K. Rose (and The W.K. Rose Fellowship)

William Kent Rose, professor of English, joined the Vassar faculty in 1953, after teaching at Stanford, Williams, and the University of California. Born in Healdsburg, California in 1924, Rose – then William Rosenberg – grew up attending concerts and theatre performances in San Francisco with his family. While his father ran a successful department store in Healdsburg, Rose seemed most influenced by his mother’s more artistic side of the family; her brother, for instance, was the cartoonist Rube Goldberg. Rose would leave his beloved “prune country” in Healdsburg, however, to pursue both a Bachelor’s and a Master’s degree at Stanford University, before graduating with a doctorate from Cornell University in 1953.

While at Cornell, Rose received a Telluride Residential Fellowship, which enabled him to develop further his interest in American and English modernist writers. He studied extensively the novelist, essayist, and painter Wyndham Lewis, whose letters he edited for their eventual publication in 1963. While a faculty member at Vassar, Rose traveled to England frequently in order to research Ezra Pound, T.S. Eliot, James Joyce, and Wyndham Lewis. As a critic, he proved most concerned with the relationships formed between these men, and he labored over his work The Men of 1914 from the early 60’s until his death in 1968. While researching in London, Rose befriended a number of novelists, artists, and critics, and developed his title as a veritable “citizen of the world.” One writer, Walter Allen, described Rose as an “informal ambassador to London” who “stood for everything that was best and most hopeful in American life.” But while Rose visited Europe frequently during his time at Vassar, and often felt “at home” in London, he never considered himself an expatriate.

Indeed, Rose relished life in Poughkeepsie, and became known for his intellectual gatherings. “Always trying to enrich the… Poughkeepsie social scene with new faces,” Rose would invite various acquaintances for lively conversation and dinner. Vassar Art History Professor Emeritus and close friend of Rose’s, Eugene Carroll, remembers Rose’s passion for novel culinary treats (i.e., espresso-flavored gelatin with whipped cream), his diverse group of guests ranging from Vassar professors to New Yorker critics to ballerinas, and, most of all, his dry humor and lucid wit. While Rose would never return to California to live, he seemed to emanate a certain “Golden Land” charm. Beyond his amusing anecdotes concerning growing up in Healdsburg, Rose had boasted an affinity for suntans, convertibles and expensive suits. As a faculty member, he had a “nearly magical ability to make people know that he… seriously cared for them,” though he found it hard to tolerate “stolid and pretentious academics” and made every effort to distance himself from such individuals.

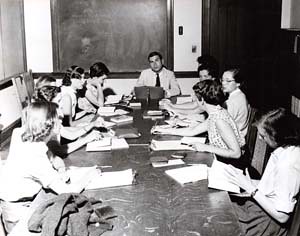

Rose favored foremost students and colleagues who exercised a talent for thinking and working creatively. While he conducted a seminar on the twentieth-century novel and a course on romantic poetry, Rose’s favorite, according to close friend Susan Turner, was his Narrative Writing class. Rose never published his own creative writing, though he did study the subject at Stanford with the poet J.V. Cunningham; at one point, he even began a novel with fellow Cornell student Charles Burkhart. What seemed most important to Rose was not his own ascent to literary fame, but rather his ability to help students cultivate their own creative abilities. Inside the classroom, “Mr. Rose” proved “intensely private,” and forever intent on ridding his students’ work of clichés and overtly stereotypical characters. All the while, Rose insisted on having his students learn from literature; he had one student teach a class on Henry James because he thought her stories cluttered with purple prose; he offered literary examples when expressing “metaphor as a technique of understanding” or “the landscape of nightmare.” Rose thereby wove literary criticism into the fabric of his composition classes. For Rose, criticism became a means to creativity.

Rose remained fiercely loyal to Vassar until his death, and was always active in the Vassar community. He became involved in various committees, including the Committee on Educational Planning (1957-58) and the Faculty Committee on the Deanship (1965-66); during the time of Vassar-Yale Study, Rose served as the chairman of the faculty elected committee (and strongly opposed relocation to New Haven), and also as president of the Vassar chapter of Phi Beta Kappa. As its chairman, Rose represented the Vassar Journal of Undergraduate Studies at the college’s Board of Trustees meetings. He also taught a seminar on Freud and served as co-director for “Classroom ’63,” a series of courses for Vassar alumnae and their husbands.

But towards the end of his life, Rose grew increasingly anxious about completing his book The Men of 1914. He won both Guggenheim and Vassar Faculty Fellowships in 1967 to support his research endeavors, but was diagnosed with a brain tumor in August 1968 and faded from public life. He disliked the “entire ceremony” of dying, Eugene Carroll remembers, and he dedicated his final energies to implementing the fellowship that now bears his name.

The W.K. Rose Fellowship, as Mr. Rose himself designated it, was established in order to afford “a worthy young artist with a chance to be free after college to get on with his work as an artist.” Rose left $175,000 to the cause, and directed that each recipient of the fellowship be given enough money to support him or her “adequately for a year.” When the prize was first distributed this sum amounted to $6,500; now, Rose fellows receive at least $30,000 for the year. In his will, Rose stressed that “maximum freedom” be afforded the artist in question, and he clarified that the prize was only open to creative artists – writers, painters, sculptors, and music composers especially.

Shortly following his death, President Alan Simpson designated a W.K. Rose Fellowship Committee, following a suggestion made by Professor Carroll, and two professors each from the Art, Music, and English departments were invited to sit on the committee. At least one committee member had to be a creative artist. The committee members opened the competition to all Vassar graduating seniors and alums under the age of thirty-six; they also decided that two fellowships could be awarded in a single year, if two individuals merited the award, but this occurred seldom.

Between1970 and 1980, the committee received from forty to sixty applications a year for the fellowship, and they awarded fourteen fellowships over the course of the decade. Certain Rose Fellows, like Ellie Daniels ’66 (one of two students to receive the honor in its inaugural year), used the award to boost their careers considerably; Daniels remembered the fellowship helping her “win a scholarship to the Villa Schifanoia” and “enhanc[ing her] credentials” when applying to teach at the Rhode Island School of Design. With the Rose, Daniels went from never having sold a painting to being able to support herself with her own work. 1976 Rose Fellow Elizabeth Spires, similarly, went from “writing ads for hamburgers, cable TV, and an ambulance factory” to writing a book of poems entitled Globe, which would be published to wide acclaim. Nancy Graves ’61 used the fellowship to bolster her already flourishing career as a modern artist.

In a 1981 issue of The Vassar Quarterly, however, Paula Volsky ’72 and Sharon Marshall ’75 described their fellowship years as less immediately prolific. Marshall fell prey to procrastination, while Volsky fought writer’s block for years after receiving the prize in 1973, but finally published Zargal The Hungry, a fantasy novel, in 1981. Kathryn Kilgore ’67, encountered similar problems with writer’s block, and used her fellowship money to move to Vermont, live in a commune, and ruminate on “very abstract theories on how the American society operates,” before escaping to Quebec, quitting poetry, and writing her first novel.

Whether immediately successful or not, though, most Rose Fellows agree that the fellowship grant afforded them instant and unprecedented freedom in their artistic endeavors. In divesting themselves of the usual part-time jobs and financial worries, many Rose Fellows achieve “the maximum of creative activity with minimum formal requirements” that Professor Rose had intended for them. If nothing else, Rose Fellowship recipients experience the ideal artist’s life for a year, in which they might travel to far-flung regions and explore, or just “look out windows, read, and wait for ideas to coalesce, all the while knowing [that they’ll] be able to pay the rent.”

RELATED ARTICLES

SOURCES

“About the Rose Fellowship.” Vassar Quarterly. Winter, 1981.

Greene, Alexis. “A bouquet for William Rose.” Vassar Quarterly. Winter, 1981.

Letter from W.K. Rose to Mr. Howard A. Seitz. August 22, 1968.

Memorial Minute for W.K. Rose. October, 1968.

Newman, Barbara. “A bouquet for William Rose: Discipline, Chivalry, and Rose.” Vassar Quarterly. Winter, 1981.

“Phillip Finkelpearl remembers Bill Rose.” Vassar College Special Collections.

Section VI of W.K. Rose’s will.

“Susan Turner Remembers Bill Rose.” Vassar College Special Collections.

Vassar College Press Release. Professor W.K. Rose. October, 1968.

“W.K. Rose.” London Times. 1968. (Obituary)

SL, 2005