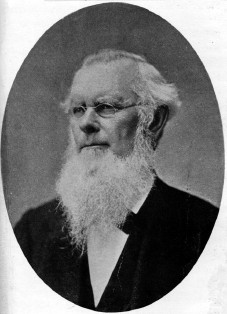

Milo P. Jewett

Milo Parker Jewett, Vassar’s first president, left an indelible mark on the college’s history by departing from the institution he helped construct before it opened. The meeting of Matthew Vassar, a wealthy and forward-thinking business man, and Milo Jewett, a conscientious clergyman and dedicated educator, was a fortunate one that laid the foundations for Vassar College.

Jewett was born in St. Johnsbury, Vermont, in 1808. Educated at an academy in Bradford, Vermont, he attended Dartmouth College where he graduated in 1828. He then spent a year as the principal of Holmes Academy in New Hampshire, simultaneously studying law under Josiah Quincy. Abandoning law in 1829, Jewett entered the Andover Theological Seminary to prepare for the Congregational ministry. There he received instruction from Leonard Woods, an influential professor of theology. Jewett attended teaching school during his winter vacations, and was recruited by Josiah Holbrook, founder of the lyceum system, to lecture for the cause of common (public) schools in New Hampshire, Massachusetts, and Connecticut. During his senior year at the seminary, Jewett was invited by the Trustees of Marietta College in Ohio to join their first faculty, which consisted of four professors. Because Marietta College was sponsored by the Presbyterian Church, Jewett obtained his license to preach from the presbytery. In 1833 he married Jane Augusta Russell.

Jewett began his professorship at Marietta College in 1834. During this time he continued his work as an advocate of the common school system. Shortly after coming to Marietta, the first State Educational convention of Ohio appointed Jewett and two other professors, Calvin E. Stowe and William Lewis, to establish a common school system. Stowe went on to inspire Horace Mann’s famous campaign for a nationwide public school system. After four years at Marietta College, Jewett resigned. In 1838 he had been baptized into the Baptist Church. He wrote of his resignation: “Having been appointed to my Professorship as a Presbyterian, I felt bound in honor to resign my place.”

Six months after leaving Marietta College, Jewett opened a seminary for young women in Marion, Alabama. The school was named Judson Female Institute upon its adoption by the Siloam Baptist State Convention, and soon became the “most flourishing institution for young ladies in the southwest.” Jewett promoted his school all over the South, writing numerous religious papers and publishing the Alabama Baptist, a church periodical. In 1855, having spent sixteen years at the college, Jewett again apparently resigned from a position on a matter of conscience. According to Judson College’s long time president, Dr. David Potts, Jewett’s Northern Baptism may have clashed with the Southern Baptism of the college and the area, and that there was “increasing animosity in the community over his position on slavery.” (Jewett was an abolitionist.) Perhaps sensing the tensions which would culminate in the Civil War, Jewett relocated to the north, offering freedom to his own servants if they chose to move with his family.

Settling in Poughkeepsie, New York, Jewett purchased the Cottage Hill Seminary after seeing an advertisement in the New York World Record posted by one Matthew Vassar. Cottage Hill, a seminary for young women, had been run by Lydia Booth, Vassar’s late niece. Jewett purchased Cottage Hill with the intention of continuing the educational system Booth had left behind. Vassar and Jewett soon became close friends. They were not only bound by a business agreement, but attended the same church; Rufus Babcock, a Baptist minister in Poughkeepsie, had in fact urged Vassar to sell the Seminary to Jewett to advance Baptism in the town. Vassar, sixty-three and retired, was at the time planning “to apply a large portion of [his] estate to some benevolent project” and build an institution that would “benefit mankind.” Disclosing to Jewett his plan of constructing and endowing a hospital, Vassar was reportedly met with this reply:

It does not strike me favorably. Great hospitals are for great cities. To spend two or three millions of dollars in establishing a hospital in Poughkeepsie, seems to me an unwise use of money. I think you might as well throw it in the Hudson River… [The plan] is to build and endow a college for young women, which shall be to them what Yale and Harvard are to young men. There is not an endowed college for women in the world. We have plenty of female colleges (so-called) in this country, but they are colleges only in name. They have no funds, no libraries, cabinets, museums, or apparatus worth mentioning. If you will establish a real college for girls and endow it, you will build for yourself a monument more lasting than the pyramids; you will perpetuate your name to the latest generations; it will be the pride and glory of Poughkeepsie; and honor to the state, and a blessing to the world.

Vassar was inspired by Jewett’s vision of a college for women comparable to the leading men’s colleges. The idea of an institution of higher education for women was not new to him; his niece Lydia Booth had suggested such an idea before her death in 1854.

The wheels were now set in motion. Jewett energetically advised Vassar on the development of Vassar Female College, which was chartered in January 1861. At the first meeting of the trustees in February of that year, Jewett was appointed the college’s first president. He was also appointed to the committee on faculty and studies, owing to his extensive experience in education, as well as to the committee on the library.

Jewett was Matthew Vassar’s chief advisor in the plans for Vassar College from 1855 to 1861. He undoubtedly guided Vassar in realizing his project to endow an institution of great significance to society. However, many of his views on women and education were not in accord with the changing views of the time. Jewett believed that women’s roles were fundamentally as wives, mothers, and teachers, and that offering a comprehensive liberal education for women would be the greatest service in educating the society at large. As Edward Linner, Matthew Vassar’s biographer, asks, “Would he have frowned upon Vassar’s graduates of the next ten years, who did not fit into this pattern?” Regardless of their goals in educating women, Jewett and Vassar were insistent on providing a rigorous educational system with a classical curriculum, first-rate teaching, and up-to-date equipment and materials.

In 1862 Jewett left for an eight month tour of European universities, libraries, art galleries to study foreign educational policies and practices. Jewett’s constant presence and participation with the planning of the school (he had given up the Cottage Hill Seminary in 1860 to devote himself to Vassar College) was suddenly removed from Poughkeepsie. This proved fatal to his relation to Vassar and the trustees of the college, many of whom disliked Jewett, perhaps for monopolizing the planning of the college and the founder’s attentions. In February 1864, many of these problems came to a head over the issue of the college’s opening date. Unbeknownst to the founder, Jewett sent duplicate letters to five trustees challenging Vassar’s proposed date for the opening of the college and called the founder “fickle and childish”. Jewett resigned from his presidency soon after his “disloyalty” to Vassar was exposed.

After his resignation from Vassar College, Jewett moved to Milwaukee, Wisconsin. There he became a leading public citizen, active in education, religion, and philanthropy. Jewett became a commissioner of public schools, a trustee of Milwaukee Female College, chairman of the board of visitors of the University of Wisconsin, and president of Milwaukee board of health, founder of an importing business, and president of the state Temperance Society. He died in 1882.

Related Articles

- Emma Church

- Matthew Vassar

- Lydia Booth

- Plaster Casts

- Vassar’s Charter Trustees

- Top Hat Scandal

- Civil War

- Presidents

Sources

“Death of Professor Jewett” 1882. Vassar College Special Collections Folder 2

Daniels, Elizabeth A. “Jewett, Milo Parker”. American Dictionary of National Biography. 1999 ed.

Jewett, Milo P. “Origin of Vassar College.” 1879.

Linner, Edward R. Vassar: The Remarkable Growth of a Man and His College 1855–1865. Poughkeepsie: Vassar College, 1984. 14-42.

LM 2005